Wu Tsang: The Luscious Land of God is Sinking

- Wu Tsang in conversation with Fred Moten, September 2016

Conducted on the occasion of Wu Tsang’s solo exhibition at 356 Mission

Fred Moten: So first of all, in my experience of seeing the performance, and then seeing the drawing, or let’s say the transcript of the performance, and then this archive of materials that went into the performance and film, and the film itself, and then recognizing the scale of it all, from something very large, like the canvas of the transcript, to the very small particularities of the materials in the archive—all of it combines in my mind to make me want to ask a question. There are two kinds of spans that I’m constantly thinking about with art. One is a span from lightness to density, and the other is from something more cosmological, in terms of its scope, to something really small. It’s a four-fold: lightness and density; largeness and smallness. The ones who can traverse and maintain movement along those axes, are those who I end up thinking of as being great. Really the first question is: Do you know that you’re great?

Wu Tsang: Haha, Fred!

FM: I wonder what it’s like. It must be a difficult thing to have to deal with. Not so much in terms of living with your own brain, but being able to move on all those different planes and scales. It makes me think of a term Charles Rosen used in regards to Schoenberg’s work: chromatic saturation. There’s certain moments in a composition in which it feels like every note that could be played is being played, a tremendous marshalling of the possible musical material in a way that’s still connected compositionally, without anything having to be left out. Rosen thinks about this with regard to music, but it also connects with color. Your film is just so colorful. There’s this one particular moment where you and boychild are on a boat, and the boat is traversing this canal with the neon… and there’s another moment where the pattern on boychild’s headband becomes almost like a flag and is waving and is almost fading or melding with the image of the water. That richness is what I would talk about in regard to density in your work.

WT: I appreciate what you’re saying, because there are so many choices when it comes to moving-image making. Especially with the all available technologies and formats, it means that you can chose a lot of different ways to communicate. For example, when I made Girl Talk with you we ended up just shooting on an iPhone. I realize now, it was because I wanted the image to fall apart, or be barely there, and also to reference intimate daily communication. There’s not a systematic way of working—I’m not just trying to make something look as fancy as possible by default. But definitely with Duilian there was a choice, at a certain point, to sort of… go for it. What it meant to take on this subject-matter in this context, became about honoring the size of the material, even if it meant having to hustle to make it possible. There were certain things the material demanded, for example filming on a boat in order to be floating between space-time and geography. Working collaboratively with many people to coalesce the poetry translations required a lot of time and energy. I wanted the film to feel like an exquisite corpse, to destabilize identities and narratives. We have talked about art in terms of an axis of lightness and density, but also in terms of an axis of beauty and horror. When I’m working, I’m always searching for a certain kind of pleasure and humor combined with devastation, and the stakes have to become high in order to make a decision.

FM: There are all these things that come into my mind in an obvious way, and that’s what makes me not want to say them. It’s not that they are not real and true, but you have to work for it a little bit. How do you do justice to someone’s story? Somebody’s story is always more than just theirs. You have to get into a whole bunch of stuff that you don’t immediately have access to. If you’re getting a story by way of one person, that means you have to do all this imaginative work to try and do justice to everything and everyone else. But even beyond the simple questions of one person’s story, there’s all these other things you could talk about under the rubric of intensity. It’s like what you were saying: it has to be as beautiful and it also has to be as terrible.

WT: Yes, totally.

FM: It’s not a balance of terror and beauty. It’s all terror and all beauty.

WT: They are not separable.

FM: But then you have to figure out a way to do it, and show it so that people can receive it in a way that does not immediately trigger a certain kind of impulse to reduce. You could be writing about some shit that’s horrible and you write about it in a beautiful way, but you also write about how that horror is completely inextricably bound up with beauty. Especially the relationship between you, boychild, Wu Zhiying and Qiu Jin. How do you create a way for people to be able to accept all of it, without having to reduce it?

WT: I’m aware of critiques, or suspicions, that contemporary art has of narrative and also of beauty, which is something that I find myself wanting to push back on. If you look at it one way, there is a certain privilege to failure or incoherence, which I can’t fully relate to. My experience has been about trying to exist and to thrive, which is something I might relate to being trans. I’m not saying that I’m trying to translate myself into something that I’m not, or to make visible, to use my least favorite word. But for me simply to exist, and the realities that I’m inhabiting— for those things to be communicated and communicable, it’s not the same thing as reducing them. That’s actually something I’m actively trying to do.

FM: It makes me wonder if there must be actually some pretty intense and irreducible relationship between being trans and what it is to be communicable. What it is to be engaged in a general communicability that is beyond or outside of any restrictive and restricted economy of reduction. This is all about what it means to be working in a way that occupies or traverses these spaces that is defined by absolute intensities, densities at the same time as absolute richness and light.

That seems to me to be the goal, the task… and I think that trans is one word for it that is not just one word among others. You know what I’m saying? I have all these shorthand ways of putting shit that I steal from other people, but what I mean is that there are other words that one could use, but none of those words is replaceable. Not only are they not replaceable, they are not substitutable.

WT: Right. One could say brown.

FM: Our friend José [Munoz] would say brown. It’s another word for it, but it, too, is not just any other word. Like you say, I think the privilege comes from feeling like you could kind of slack off.

WT: There’s a position from which some can assume legibility, as a point of departure.

FM: It’s not about achieving some absolute success or something like that. The absoluteness is in the attempt, not in the achievement. The privilege that you’re talking about is the privilege to fail to try hard! Our lives are lived in the context of an absolute brutality, and your recourse to beauty, someone might say, is a way of deflecting that brutality. But there’s no way for us to understand anything like the intensity of the brutality, if you slack off on the beauty. Each one makes the other possible to see or to know. I look at what you’ve done and I can tell with each individual piece that attempt is there. But also the range of material, the range of things that you make across these different genres, it all feels like a massive attempt at doing justice to this whole field of life that you’re a part of, imbedded in.

WT: I hope I’m not reducing it to something simplistic like our “pain is beautiful” but it does make me think of ways I want to challenge critical practices that try to separate these things. Maybe beauty falls into the category of pop, or maybe trying hard gets conflated with succeeding, but I think art should challenge, make people uncomfortable, and there is a certain safety, or even let’s say problem with focusing only on the struggle. Only people who have not actually struggled would see others as downtrodden.

FM: Artists are always working with different levels of awareness of this problem. Another technical term would be the necessity of refusing reductiveness. It’s a mathematical problem on a certain level, but it’s not something you can get at by way of these sort of rote calculations. It moves by trial and error and improvisation.

WT: Maybe this is a way to talk about artistic process. It reminds me of a conversation we recently had about how writing and performance are inseparable in your poetry. Specifically, you were talking about how, when you’re working on a new poem, you read it out loud over and over again. If you stumble, it’s not a mistake; it means the language is not right. You re- work it until there are no stumbles, until it comes out of you, or you’re able to get out of the way of it, as you said. So your performance is a rigorous process, but it doesn’t come from performing that rigor, it comes from an openness and attentiveness, and of course repetition. I can relate to that process, because I’ll spend forever researching for a film, even though by the time it actually becomes a film, most of the material is not there. The research becomes embedded, but not necessarily on the level of the image or the story. Actually with Duilian, it was specifically a language thing. Because I was working with five languages—four of which I don’t speak, and I can’t read Chinese characters. So I was fumbling through so much memorization in order to arrange the script and edit the film. When I edit, I usually prefer to start over from scratch, rather than re-work a scene. The process feels almost closer to musical improvisation than filmmaking.

FM: In regard to music or spoken word, people would say that it all seems so effortless. But effortlessness is not a quality that accrues to lack of effort.

WT: That gets back to the lightness and density thing. Because effort does not culminate in something rehearsed or memorized. Each time you read a poem it comes out completely different.

FM: The difference emerges that way. It’s just like in the martial arts practice in your film. There’s one cool moment where one of the martial artists is showing boychild a particular way of standing and holding the sword. And then it cuts to another moment where the other four women [the sword sisters] are all in formation, about to begin an exercise in a specific position. What was amazing, was the absolute non-identical nature of each performer’s perfect occupation of the proper position. That’s something that only emerges from not only work or effort, but also from a certain kind of ritual practice. I think about this more-so with regard to blackness than I do with regard to transness, but I’m beginning to think that these things converge in an irreducible way. They can’t be thought separately from one another, because both manifest themselves in regards to ritual practice. I don’t think about blackness as an identity. I think about blackness as a ritual practice and I feel like I should think this about transness too.

WT: If I had to say something about identity, I also think of ritual practice. I was recently asked to write something about identity for a publication, and the first thing that came to my mind is that identity is the act of putting yourself together each day.

FM: If identity is the ritual practice of putting yourself together every day, the ritual and jurisgenerative practice of putting yourself together every day, then it manifests on the most specific level under the rubric of dis-identification, as José taught us. The way you put yourself together every day is the way that you take yourself apart every day. In other words, dis- identification is this practice by tearing one’s self apart. You can see it at precisely that interplay between the fighting and dance that is such a big part of your film. These modalities of dancing and fighting are really about a ritualized activity of ripping your body apart. It almost feels like…

WT: Like your limbs are coming off!

FM: You’re slicing your own limbs off. In that opening scene, you see the first swordswoman and this tremendous twirling and flash of the sword, accentuated by its flexibility and thinness- —it’s as if you have a whirling circle of matter that keeps slicing parts of itself off that almost immediately recoalesce. So, putting one’s self together every day is inseparable with tearing one’s self apart every day.

WT: In that opening scene, the voiceover is a famous line of Qiu Jin’s poetry, but here it was translated and performed in Iloco [a Tagolog dialect]: “My body will not allow me to mingle with men, but my heart is far braver than that of a man.” I’m just thinking about what it could mean to segment the body into parts, and how those parts measure up to one’s assessment of power. What limbs can we sever, or momentarily conjure, to constitute our place in this world?

Wu Tsang and Fred Moten collaborate and cohabit the roles of performance artist and poet. Recent projects include films “Miss Communication and Mr:Re” (2014) and “Girl Talk” (2015), and an upcoming Performance in Residence commission, “Gravitational Feel” for Edition VI for If I Can’t Dance, Amsterdam.

- Select Reviews

-

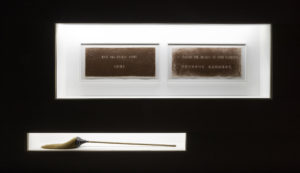

Wu Tsang and boychild: YOU SAD LEGEND

August 14, 2016