John Kaufman “Faultline” at The Vanity East

- A conversation between John Kaufman and Andrew Cannon, January, 2014

Andrew Cannon: The Vanity East show includes three of your reflection holograms of rocks?

John Kaufman: Yes, multicolor reflection.

AC: I read about your pseudocolor process in your article “Life in the Lab” (1992) that was published in Leonardo. You change the colors by controlling the swelling of the emulsion?

JK: Yes, that’s right. What’s really helpful for anyone wanting to get into holography, or just to learn about it on an accessible technical level, are papers published by SPIE (The International Society for Optics and Photonics). They had some symposiums back in the 80s and 90s at Lake Forest College in Illinois, and even more recently, but the core ones were in the 80s. The papers from these conferences were really good, especially for the pseudocolor technique. I had some early papers on that. SPIE actually has a conference coming up in February in San Francisco. They’re big in optics and electronics and publish papers on a wide range of subjects, not just holography.

AC: There were other places too, like the School of Holography in San Francisco and the Museum of Holography, that worked to breach the divide between the scientist and the hobbyist in a generous way.

JK: Right. I think it was 1971 that I went to the Exploratorium in San Francisco, and they had an exhibition of holograms, which led me to take a holography workshop there in 1974 taught by Fred Unterseher, who co-wrote the popular Holography Handbook. It was a good introduction, but that’s pretty much all it was. The stability requirements of holography, that even microscopic vibrations can ruin an exposure, was one of the problems with the Exploratorium since someone in the hall had a big bass drum. Our first project was to set up an interferometer to test the laser, and we just sat there and watched the vibrations from the drum blowing the fringes around. We had set up inner tubes on the floor and a sand box on top of them to function as a rudimentary isolation table. I soon took another course from Lon Moore who had a little studio in San Anselmo, and I just worked from that.

AC: Holography was about a decade old at that point.

JK: Yes, and what was good about that time was that Lloyd Cross, one of the early workers in holography, developed this sand table system for isolating vibrations, which was a substitute for a much more expensive system being used in labs. It allowed someone who did not have the budget of the scientist to set up something in their basement. And a lot of people were doing that. Information was freely shared.

AC: That was 1968 when he came up with the sandbox with Gerry Pethick, and then he went on to start the School of Holography in 1971. And while we’re on the subject, we should talk briefly about the history of holography, starting at Lippmann or Gabor, and then also the technical requirements of what makes a hologram.

JK: Good question! [Laughter.]

AC: For the layman!

JK: It has been since the mid-90s since I was in it, so even remembering all the details of the history is tricky. Holograms in general are still a conceptual difficulty for a lot of people because what you are doing is shining light through a photographic plate, and that light is bent into a wave front that is identical to your subject. And how that is done is almost like, “Whoa, that’s great!” It’s hard to figure out in one’s mind exactly what is happening, so you just have to accept that it happens. Usually what’s happening is that you have what’s called a pure bit of laser light, coherent light. All of the waves are in sync with each other. Part of that light is split with a beam splitter to illuminate the subject, and part hits the plate directly. The two wave fronts meet at the plate’s emulsion and record what is called an interference pattern. When you shine the laser light back through the processed plate, the laser will be diffracted recreating the wave front from the subject, which constitutes an exact likeness of the subject. It’s like dropping stones into a still pond and creating ripples. You have the little wavelets of two disturbances coming together, and at those places where the crest meets, you get a bigger wave, and where the crests and troughs meet, you get nothing. That is happening photographically. Where the crests meet you get an exposure, and where the crest and trough meet you get no exposure, and what you end up with are microscopic fringes that can diffract light through them on the crosses. So there is interference of light in making the hologram and diffraction in reading it back.

AC: And so one difference between a hologram and a photograph is that holographic emulsion contains no pigment. It is additive color rather than the subtractive dye process.

JK: That’s right. With the transmission type of hologram, when white light shines through it, it will break up into the spectrum. With the reflection hologram, the type that I do, they’re very wavelength selective. That depends on the interference patterns, not like a fingerprint but more like little layers within the thickness of the emulsion. The spacing of those microscopic layers determines which wavelengths reflect back. It’s like the color of a hummingbird wing or an oil slick; color with no pigment.

AC: Had you studied photography?

JK: No, I was mostly self-taught. I was in the Peace Corps, teaching on a little atoll in the middle of nowhere, literally. I had a friend who printed my rolls during one of my breaks, and I was in the lab with him and just saw him work. It was a pretty straightforward, by-the-Ansel Adams-book, read-the- Kodak-handbook kind of a thing, and then a lot of trial and error, which is the way holography was too. People were exploring it. Some people were scientists and explored it rigorously, and some were trial and error types like I was. We all just sort of found our way.

AC: There is a history in holography of artists working as scientists and vice versa. People like Lloyd Cross were working on a groundbreaking technical level, but also thinking about it aesthetically and politically.

JK: True. These conferences that I mentioned that were in Lake Forest were really instrumental in keeping holography together and advancing during that period. It brought together artist-homegrown- holographers as well as scientists into a fairly loose environment. Everybody talked to everybody, and no one…well, some people kept secrets. [Laughter.] There was a lot of information sharing. And it helped. You saw what people were doing, and it spurred things along. That was the way the School of Holography was too, because Lloyd had his scientific rigor, but his guiding light at that time was to move it out, to get as many people making holograms as possible. He, along with students and other holographers from the school, were instrumental in the development of the multiplex hologram that was quite advanced for the time. It involved taking the frames of a moving picture film and making

each one into a narrow slit of the hologram. So in the hologram you could view the entire length of the film. Each eye would see a different frame and put it together in 3D. As you moved around it, you saw the entire few seconds of the film.

AC: And his famous example of that was “The Kiss.” As you walk past the hologram, a green 3D woman blows a kiss and winks.

JK: Right! [Laughter.]

AC: And he did it with a do-it-yourself group-think style.

JK: That is the whole sand table ethos. In my studio, most of the equipment comes from the Ace Hardware store in Point Reyes Station. It’s of that level. It’s all PVC pipes, T-squares, right angle iron stock, and C-clamps.

AC: The papers published in the journal Leonardo by holographersfrom this period had a similar ethos. They were writing about their own work, interpreting and contextualizing it, but then also presenting extensive technical information, essentially saying, “This is how you get the same results as I did.” Similarly, in your paper you published with them, you wrote a lot about the gelatin mounting of your films onto glass next to a paragraph about finding the perfect piece of seaweed to record.

JK: Oh God, that was such a messy, time consuming, error-prone way to make a hologram. The glass was not stable enough until it was about a half-inch thick, so I’d have to have a lot of storage to keep that many glass plates. So I rethought, and started mounting the film on glass so that it could be removed later and stored. Most of those were what are called shadowgrams. Basically what the subject is in a shadowgram is a big piece of illuminated diffused glass. If you look at it from one side, you look through the image plane and see this bright, even-colored rectangle, which is the diffuser glass, in what is called the virtual space. If you flip it over, you get what’s called the real image, where that glass is now projected in front of the film in a space closer to your eyes. Once your eyes get into the same space as where the diffuser glass was, that light completely fills your vision and the whole film takes on a glowing color throughout. It almost looks like a colored foil. Then you can put objects to be recorded between the planes, and they are silhouetted at different spatial depths.

AC: Did you initially think of holography as an artistic medium?

JK: Yes. I wanted to make holograms first, and then find places to sell them second. The first place I sold them to was the Exploratorium actually. They bought some 4×5” reflection holograms I made in the late 70s. I didn’t get my studio together until 1977.

AC: That was at the same time as the San Francisco School of Holography, which was still going at that point. Was there a community of people in San Francisco and the surrounding areas making art with holography?

JK: Yeah, I didn’t know that many people until Holos Gallery opened on Haight Street in 1979. Gary Zellerbach was running it, and he had regular exhibitions and openings, so people would gather for those. It was a good time for Bay Area holography. I was not associated with the school and hadn’t come up through the system, but I knew them tangentially. We were all spread out. In Marin County there were two other people.

AC: So here you are, a holographer who positions his studio on the San Andreas Fault, which is infamously vibration rich.

JK: Well, I figure those tectonic disturbances are exposures I lose. One of the ways to make an isolation table is you set the sandbox on inner tubes and they’re supposed to isolate the mass of the table top from the rest of the environment. But I found that it was quiet enough around Point Reyes and that I did not even need to use the inner tubes after a while. The only thing I would listen for was a car coming up the road, which was not that frequent. Air traffic too. The vibrations from the planes overhead could cost you.

AC: If you look at artist and hobbyist holography, most of the subjects are inanimate objects, since a plant or animal would have too much inherent vibration. It’s only with incredibly expensive pulsed lasers that one can make pictures of moving things. One of the first widely seen holograms was of a toy train.

JK: Holographers have a tendency to go for kitsch. Common things are interesting, but a lot of the kitsch people were serious; there was no sense of irony to it. The tumbling dice and the coins and the eyeballs…

AC: You were making holograms of rocks. An incredibly stable subject? [Laughs.]

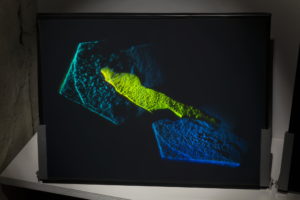

JK: I was trying all sorts of things. I was using tree branches, butter, waffles… I tested the limits occasionally, and often the limits beat me. [Laughter.] You always want to see what you can do. I once made a hologram of a feather, and most of it is pretty good except for the very tip of the feather is not quite as bright. It was moving just a little bit. The rocks were good. I have always liked rocks. They work for me. The geology of Point Reyes is very different from the geology of the mainland. Most of the rocks that I was using were granitic and came from Point Reyes. Though I think I am showing ones from the mainland this time. I was splitting the rocks along their natural fissures and putting them back together holographically, which is why I am calling the exhibition Faultline.

AC: In your Leonardo article, you wrote about walking the beach and looking for objects to place in your compositions, and if you look at your work, there is a lot of foraging, bringing in objects that are found…

JK: Yes, I work with found objects, whether they’re domestic or in nature. It is not just, “Hey, look, I found it, and I’m going to make a hologram of it.” I am working with it after that. A lot of the early ones were just one color reflection where I simply wanted to see how they looked holographically. How they transform. It was part of learning about holography. Edward Weston was key for me in thinking about looking at objects and seeing them deeply.

AC: Later you were experimenting with multiple exposures and superimposition, as well as controlling the color. You were placing the film in sculptural situations as well.

JK: The film itself became much more of an object than before when I was working on plates. With the glass plates, one thinks of them more as a window. Objects appear as if through a window. When working on loose film, it just has different qualities, and the emulsion comes to the fore as a thing in itself. I would print onto the film, for example, by coating ferns with a gelatin-swelling chemical and then impressing them on the emulsion. Then I would pull the fern off and let that chemical change the

color of the emulsion and see what happened with that. In the shadowgrams, I was almost always working with both sides of the plane. There would be diffused light reflected in the viewer’s face, and then there would be light in the virtual space as well. In that distance, which could be a meter or more, there would be different spatial layers.

AC: In the 80s and 90s when you were focused on making holograms, you were producing something that, from its inception, was too specialized for the general public to understand. There was a serious community producing art holograms, but the audience, or an informed one at least, must have been fairly limited.

JK: Until Holos Gallery started, there was not much in the way of an audience. The East Coast had a relatively large scene for rainbow holography since Stephen Benton, who developed the process, was at Polaroid and MIT and was a mentor to many. The Museum of Holography, founded by Posy Jackson in 1976, was as close as holography ever got to having a real art venue. But like most holography then and now, it confused itself with the scientific ends of things to an extent that often in exhibitions, what is art and what is scientific demonstration were unclear. That can be a happy confusion, but it certainly did not help find a broader art public. Holography is always marginalized as either scientific curiosity or kitsch memorabilia.

Boston, New York and San Francisco were the big spots, and there was some holography going on in LA, but not a lot. And there were other places too. Chicago’s Lake Forest College had Tung Jeong teaching holography, and he was a great educator. He started the symposiums on holography, which were under the auspices of SPIE and brought a lot of interest to the Chicago area. There was a museum in Chicago as well, so there were these outposts all around. Where there was a lab, people gravitated towards it to use it. Artists found ways to go in for some arrangement, and there were a few labs geared towards art, like the Museum of Holography, which also had a lab and hosted an artist in residence.

AC: It is interesting to look at holography now. Most people have never even seen a real reflection hologram. We’ve all become familiar with holographic foils and mass-produced rainbow holograms, but an actual homemade hologram is a seldom seen thing.

JK: There have been very few exhibitions in recent years that would expose large numbers of people to holography, and so they just do not know what they are looking at.

AC: The Museum of Holography closed, and MIT, which bought the collection, apparently shows very little of it.

JK: No, they do not. It has become a historic artifact. Holography was usurped by a lot of things that were happening in computers. With computer modeling programs, the word 3D was co-opted to mean a perspectival drawing on a computer. Now, even the word hologram is co-opted on TV, like CNN has a “holodeck” and Tupac appears on stage as a “hologram,” but it is actually just a 19th century theatrical effect—the Pepper’s ghost illusion.

AC: The scientific application of holography became incredibly influential in industry and physics, but in daily life, the paradigm shift in images that holography promised never came.

JK: There are some small holography kits that are sold, and you could make a hologram at home fairly easily now, but it is still for the science geek rather than the artist. I stopped making holograms when AGFA stopped producing high quality plates. In the end, their 30x40cm plates must have been $100

each. They were getting expensive, and so the number of holographers was limited and the number of holograms one could make was limited. It might be that we just need to wait a couple of decades until computing power gets to the point where you can have good digital holograms that everyone can do.

AC: This reality is at odds with the literature surrounding holography from its beginnings that predicted the inevitable totality of holography in culture. Compare the paradigm shift to that of the introduction of perspective in painting or the advent of photography.

JK: We were quite idealistic about the whole thing, and over time it was, “If only we could get a better lighting display system, then everything would work out.” I even see that written now, where they talk about 3D for televisions. “If only you could get rid of the glasses, then people would want it.” It is like my issue of Popular Mechanics as a kid that promised individual flying cars that you park at your house and can use to fly off to anywhere.

AC: The French theorist Jean Baudrillard, who apparently did not like holograms, wrote in his book Simulacra and Simulations (1981), that while holograms, existing in three dimensions, seem to be closer to the real object than a two-dimensional image, they instead make the viewer more aware of the missing component of time, which perhaps creates that sensation of the uncanny stillness of even inanimate objects. He is arguing that the pure similitude is non-meaning, which…

JK: One of the great things when you are doing a transmission hologram is that when you put the processed plate back in the plate-holder and shine the laser light through it, you have the actual subject there and you have the holographic subject occupying the same space. When you pull the real object out, and there is still the holographic image…every time your mind and body does this quick little jerk, and you feel that sense of “How can this be?” People used to refer to holograms as being tomb-like, and holographic portraits as ghostly. There are these associations that people cannot give up. Maybe it is so easy to dip into them that they will not think any further than that.

AC: Who was buying artists’ holograms at that time, and what happened to the collections?

JK: That’s a good question. I sold a lot of holograms to various galleries during the 80s in the US, some in Japan, a number in Europe. Some of the galleries only showed artist-made holograms, while others. sold every kind of hologram that is made, which included a few art holograms on the wall. All different mixes of that. Many times I had no control over where they were being shown or how they were being shown. Holos Gallery, which I loved, had a counter with dichromate pendants of all various types. Some of it was pretty bad, and unfortunately the art gets associated with it. One hopes that the art transcends it, but I think the average person would be confused.

AC: Who were the collectors who were interested in the medium?

JK: Oftentimes the collectors were the people running the galleries. They would have some customers that they would sell to, but for the most part they were collecting and showing them because they loved them—the same reason that we were making them. I am not sure what has happened to all those collections. Matthias Lauk, who has passed away, amassed a large collection in Germany. He started the Museum für Holographie, and he did a good job. He would put together shows of pretty high- quality aesthetic work and show them around. He ended up selling his collection to the Zentrum fur Kunst und Medientechnologie in Karlsruhe, Germany.

AC: You were saying that you haven’t been making holograms now for quite a bit.

JK: Right, I stopped making holograms in the mid-90s when AGFA discontinued their plates. In 1989 there was Gulf War and then there was a recession. Almost all the galleries closed and there just was not enough happening to make my business model work anymore. I produced for a few more years, mostly film things, but also some glass plates. I just did not feel that I had the energy or the desire to buy many thousands of dollars of plates before they were discontinued, and then have to store them in a fridge for years and years. I got a 4×5 view camera figuring I could do something else a lot easier.

AC: Are you doing photography still?

JK: Yeah, I did the black-and-white view camera stuff for a few years. I was strongly influenced by the photographs of Jaques Lartigue. Much of his work, which was done at the turn of the century, was shot as stereo pairs. In Paris, I saw an exhibition of his work where they produced big blow-ups of the stereo pairs and used large mirrors that you would put your eyes up to the apex of and look straight ahead, and you would see the 3D image in front of you. A clumsy way, but still very effective for viewing the stereo pairs. So I started doing that with my view camera. I did not really show them because the mirror display system was way too cumbersome and delicate. As digital cameras got better, I got two digital cameras and starting working with those. Now I have a relatively inexpensive video camera. I had not done 3D video before, but my grandson was just moving too fast for still photography, and I got this video camera and a digital projector so I can project onto a screen in 3D.

For reading, those journals from the International Symposium on Display Holography were always really good at Lake Forest, and then I don’t know if people have put online any of the back issues of Holosphere, which was the newsletter for the Museum of Holography. Those were great. Then in the Bay Area there was L.A.S.E.R. News. Those had scientific and newsy gossip. The whole range of stuff. They actually give a pretty good view of what the community was like. Except for the marijuana, of course. That was a big part of it. We have to admit it.

AC: It was a psychedelic time.