Brian Sharp

- Brian Sharp in conversation with Jon Pestoni

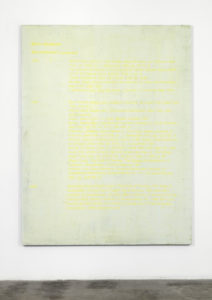

This conversation took place on the occasion of Brian Sharp’s solo exhibition at 356 Mission.

Jon Pestoni: What preparation goes into the work? For example – when I walked into your studio I saw sketches, which I’ve never seen before. And they were little cartoon-like sketches with a border around it. Much the way an architect would do. And then there’s a shape inside maybe it has some color in there.

Brian Sharp: These paintings are made with a handful of “moves”; stripes, numbers and text, tree shapes and fruit shapes, smudge outs and rollovers. The sketches came after the paintings, so they aren’t prep sketches. I wanted to figure out if there was any cross-pollination I could explore. How I could use the existing imagery to get into a new painting. After I had a few paintings resolved and I started taking them apart to figure out what each one was made of – three moves in this one, four in that one, and two moves there. So those little drawings are basically a single move, or a card in the deck.

JP: Are they always vertical? What is the height?

BS: Yes. The height is 68 inches, which is how tall I am… I don’t know if that’s important or not… it’s a measurement people have used in the past.

JP: And on linen?

BS: Yes – I don’t use it because of a specific tooth or surface or the way it takes paint off the brush. I size it and use a drywall taping knife to apply many coats of gesso in full strength so the “fabric appreciation” aspect of it really is irrelevant… there’s something about the color of it, and the relationship it has to the wall, it separates the “painting” part / the surface from the wall. It’s a color thing, it offers more of a break – the color of canvas is so close to the color of the wall and I favor the separation the linen provides.

JP: For the striped paintings, is the width of the stripe similar to the depth of the panel? Your eye scans the faces of the paintings and then as it comes off a painting it gets that one last stripe before it hits the wall.

BS: It works that way in some of them. The stripes are really just a way to have something new to deal with, a way to fracture the surface, instead of a complete paint out/over, I use a large ruler and a spackling knife and scrape the stripe out. The depth of the canvas is actually more specific, it just so happened that the width of the knife is the same as the depth of the panels. But this is something I really like: finding a commonality through working…and this connection, knowing Stella’s striped paintings and his specificity – choosing to make his early paintings with stripes the same width as the depth of his stretchers as a way of uniting or getting information out of the support to inform the imagery, I guess it’s like these three things came together and I liked that…I really try to stay busy and look for things, work and pay attention and find relationships – sometimes from the paintings, sometimes from somewhere else.

JP: Are these compositions motivated by the tools you use? Tools like drywall knives, rollers, things like that. In some of the paintings there is text and definitely small brush work. In other paintings it feels like the paint was applied with an application other than “fine art.”

BS: Yeah, it’s true, I can be handy and I really enjoy odd jobs – building cabinets, or simple furniture – those things have a function and when it’s functioning it’s done. This also means that in addition to brushes and palette knives, I have other tools around, and these have definitely come into the work. Not because I want to make paintings about construction or complications or pleasures of a vocation but because they are the tools at hand for the most sensible, economic application of oil paint to panel.

JP: Do you ever make a scrap book of images or pictures that you like before you make a body of work? Things that maybe you collect or does it all come from responding to previous painting moves?

BS: I don’t keep a scrap book, I’m not that organized, I do though have boxes and boxes of stuff that seems too important to trash and this work comes a bit out of that back catalogue, in very random ways. As for the other part – as a catalyst for the recent paintings, I’ve started them where the previous body of work ended. For instance – if the last move for a previous body of work was to put spots on them – I start the new paintings at that place or resolution, and use it as the initial set of imagery to begin the questions and answers. It’s a way to…

JP: Open it up?

BS: Exactly, and it gets knocked back and forth, painted, painted out, there’s a dialogue.

JP: So which is the real you? Bringing it in, or taking it out?

BS: I wish I knew. I make problems so that I can solve them, a mess to clean up, the back and forth and the conversation between the “me viewer” and the “me maker” is a big part of the work. So both… it’s always two forces for me. I start with a history and there are moments when I go, go, go, and I don’t get anything, and next day I wipe out / paint out. It’s always this call and response, sometimes a painting sits for weeks on the wall and I don’t know what should happen next…sometimes those are done…other times the moves lead very quickly to the next move.

JP: How do the paintings develop from one body of work to the next? If at all?

BS: I work a lot but I don’t show often, so there’s some growth and development that’s wrapped up in storage. I think about making a skyscraper… it’s fascinating to me while a crane is mounted to the top of this structure and steel is being welded, the skeleton is being made up top, the first floors are already dry-walled, plumbed, carpeted, marbled, whatever – essentially functioning as we understand how a building is supposed to – so the practice is like a never ending skyscraper, only I have the benefit or luxury of improving each floor because of what I know about the floor underneath it. It would never work this way for architecture. I see it as an ongoing, everlasting project. The exhibition is when the hand gets pulled out of the deck.

JP: What are the steps to make these paintings different from one another?

BS: The resolution for one painting rarely resolves another painting, what it does though is give me something to answer to, something to negate, something to spark another move. So there is repetition, just not repetition, usually, in resolution… I’ve thought about the work differently in the past couple of years, I used to let the parameters the work set dictate what could or couldn’t get into the painting, I would leave things out because it seemed unrelated or something. But then I realized that this is just a painting – there are no rules. I was talking about collaborating on some paintings with a painter friend and I always seemed to work myself into a place where I could anticipate what I thought his move could be, how he would respond to my marks and I was like – wow, that would really finish this thing. We never got around to collaborating but at a certain point I realized me being him was just me being a more objective me and why shouldn’t I just go for it? It was like collaborating with myself – which, as you know, a painter and I guess other artists too – there is a lot of conversation between painter and painting. A lot of offense and defense… between a person and stuff but also right there on the surface, a person controlling and negotiating stuff…

JP: One thing that makes it look like they go together is that they’re all the same size. It seems like you are trying to guide the viewer in how to look at the paintings. It’s like a cheese plate: there’s a place to start and then you move in that direction clockwise or counterclockwise. Are you activating space by having the viewers ping-pong around the room?

BS: There is not a starting point. There will be I suppose, but it’s really based on formal decisions. I am very particular about the installation part of the work – for me it’s like the last step is putting it together – what kind of rhythm, what kind of sense I can make out of it, a show is different than a group of paintings. It is like a cheese plate but with a different palette.

JP: While they look different, there is a thread. Good paintings tend to stand on their own and also play well with other paintings. Your stripe paintings can function as a break in the installation. We also return to the size of the tools: this is the width of the knife; this is the brush size. And then in the next painting you are using all these tools to different effect.

BS: I’m not always in the same mood, my music choices vary day to day, I don’t always eat the same thing…in contrast, I’m also a creature of habit. I am intrigued by dysfunction but I ultimately want to make something worth looking at, so I think I tend to take these things on a trip and bring them back home…other times they find themselves on that road.

JP: But do you start with what you know?

BS: I would say not all the time. I don’t want to sound cliché but I think there’s some real truth to making yourself vulnerable, working out of it, putting myself into an uncomfortable position and figuring it out. Painting is such a solo endeavor. I’m by myself all day, I ask the questions, I answer the questions, I have this conversation with myself and in an effort to keep that conversation interesting I push it to uncomfortable places and find my way out or just stay there and keep it in that uneasy zone. We’ve talked about honesty and truth and being real, and not to sound cheesy but painting can be revealing, or it feels that way, or I want it to. They’re like sandwiches and each one is different, but they’re all sandwiches made of the same stuff, some with some of this and some with less of that… so what does it reveal? Uncertainty? Bad decisions? Insecurity? Comfort with all that? I guess I don’t really know but the picture is affected, and I think it’s what makes it and keeps me interested in the painting.

JP: If there was one thing that you hoped the viewer walked away with after seeing this work, what would you want that to be?

BS: I like a slow reveal that continues to provoke and I like finding answers at extremes. Take David Byrne’s dancing in the Talking Heads video for “Once in a Lifetime” – it doesn’t make sense all, but it makes all the sense in the world. It’s seriously ridiculous and ridiculously serious. I haven’t really touched on this but I think sometimes you have to go way out, to the point of silly, and bring it back to get something earnest. And the questions sometimes are more interesting than the answers. I don’t know if I have the answers. I guess I want people to deal with these things the same way they would deal with other stuff, take it in, make connections, make assumptions, make sense or don’t make sense of it, you know – it’s here and it’s real.

JP: You once told me that someone responded to your paintings by saying they were about nothing. I’m wondering if that response is in the work before it starts. Are you interested in negotiating between making something and nothing in all of these paintings? You’re giving us something and taking something away at the same time. You’re not trying to pin anything down, but with this back and forth of nothing and something, you get a painting to look at.

BS: Yeah perhaps. They are what they are… a by-product of working. It reminds me of a quote that I recently found in one of those boxes of stuff, and I’m not sure who said it (maybe Peter Acheson) but it seems very fitting and it goes like this: “Painting is a search for a language but then a push beyond whatever place one has gotten to… testing over and over if the container holds water, spirit, meaning. So subversion is a key methodology. Hence, no real expectation of having a style but rather the presentation of a sensibility, and the good old-fashioned persistence of a practice. This is what the audience needs, the confirmation of people practicing.”

Jon Pestoni is a painter based in Los Angeles