Wayne Koestenbaum: A Novel of Thank You and Other Paintings

- Wayne Koestenbaum interviewed by Lia Trinka-Browner

Conducted on the occasion of Wayne Koestenbaum’s solo exhibition at 356 Mission.

Lia Trinka-Browner: Many of the titles of these paintings, including the title of the exhibition, are taken from novels – Gertrude Stein’s A Novel of Thank You, Nightwood by Djuna Barnes, Good Morning, Midnight by Jean Rhys, to name a few. All the titles that I recognize are books by women. Can you talk about employing these specific titles?

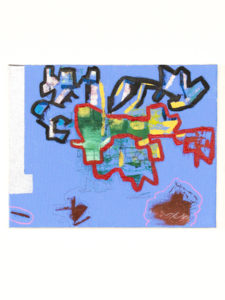

Wayne Koestenbaum: Seven of the paintings in the show are “novels.” Crowded, incident-packed, meandering, digressive, unplanned. Conglomerations of marks. Anthologies of moods. Messy and non-figurative, but threatening at any moment to spill into image. Instead of spilling, the paintings dither in the accident-prone neverland of the vaguely biomorphic and hieroglyphic–marks and shapes that slightly want to be plot-oriented and maybe (if they’re headstrong) gendered, but that, instead, linger in a mark-for-mark’s-sake limbo of giddy supra-gendered feeling. I named most of these paintings after capacious and category-defying works by modern women: Gertrude Stein’s A Novel of Thank You, Jane Bowles’s Everything Is Nice, Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood, Clarice Lispector’s Àgua Viva, Colette’s The Vagabond and Break of Day. These are books that tell me how and why to live. They tell me how and why by foregrounding the pleasure or distress of writing, and by describing the asocial zones of non-belonging that states of pleasured or distressed writing can trigger in the maker. When I finished the first of my anthology-of-marks paintings, I decided to call it A Novel of Thank You because I wanted to thank the painting for allowing me to make it; I wanted to thank the paint tubes for containing pretty paint; I wanted to thank Gertrude Stein for showing me how to find happiness in making; I wanted to signal, with the word “novel,” that I was writing my paintings, and that they were coming out of a demonstrably jouissance-oriented (yet pedestrian) world-view that was ratified–for me–by Stein’s novel. I made these paintings–the novel ones–slowly, each day adding a few marks, using paint left over from other tasks.

LT: I think the first thing I notice about this show is the color palette and the brightness of the work. There’s a lot to be considered in terms of saturation, flatness, and bold line-making in these works. What is your process when you paint and how do you decide on color, line and mark-making?

WK: I’m casual and deliberate. I try to be punctual in my painterly attitudes, but my version of painterly punctiliousness has a built-in imprecision. My paintings might look like carnivals, but I try to be careful and organized in my methods. Color is key. All of my thinking and decision-making about color happens sub-verbally, so if I were to narrate how I make a decision about color, I would need to write a novel about the decision. I have opinions and feelings about pink, blue, red, orange, green, purple, brown, yellow, white, black, grey (am I forgetting somebody?), and all the gradations therein. I have opinions and feelings about each specific tube of paint or each marker or colored pencil. The biography of radiant turquoise contains pathos and bathos. I put a color or colors down and then I have a feeling in response, and then I need to correct the feeling with another color; thinking and acting within color, I’m operating in a force field of images (sky, land, bodies, architecture, grass, cloud, jumper, pill, cup) and affect-symbols (happy, sad, turbulent, disgusted, sleepy, tingly). Colors are like adjectives–they plump up or diminish the noun–but also are like verbs because colors animate and send spinning the semi-story.

I have a fondness for outlines, but also for lines that approach the hieroglyphic without ever committing themselves to becoming a linguistic sign. A line is a specific wish uttered by a hand or a mediating instrument, when this hand/instrument confronts an accident. Sometimes the accident is color or volume, and the line must encounter that accident with a correction or an embrace. Sometimes the accident is the paper or canvas or wood surface itself, which the line annotates, consoles, upbraids. Line and color are active processes of investigation; line and color are thinking. By painting, I am trying to think through line and color without letting brute concepts stand in the way of the body-mind’s limber associative traffic.

Simplest answer: I use colors that reinforce my sense of being alive rather than dead.

LT: I know you’ve spoken about this before and I’m sure everyone asks you a variant of this question since you started painting, but can you talk about your writing and your painting as different or similar modes of creating? I think you mentioned in an interview a few years ago that writing is your public self and painting is your mistress. Is that still true?

WK: The difference, for me, between painting and writing, is like the difference between avidity and coercion. To some extent, a reader must be coerced into finishing a sentence or a paragraph or a poem. Reading is a bother. (As is writing.) The reader’s mind may often wish to stop reading; and writing, as a seductive gambit, must always urge the reader to find replacement-consolations in verbal sounds (dentals, labials) and in syntactic whips and waves and shocks and curves. All so indirect! Painting, in contrast, confronts an eye (mine, a viewer’s) hungry for immediate sensation. A viewer is not necessarily pleased by a painting. A viewer may well wish to stop looking at a particular painting. And yet: the moment of initial contact with the painting has the potential to offer physical gratification. I love to write and I love to read; both processes give me physical pleasure, or forms of pleasure that are metaphorically somatic. But painting, like coffee or wine or a dinner roll, is right there, offering its intoxication. The dinner roll could be stale. But it’s still a dinner roll. I give paintings–mine, too–credit for an essential right-to-exist; the palpability of their liveliness, their claim to existence (do not kill me!), breaks my heart, even when the painting isn’t “good.” I like making paintings because I like to produce living objects, even if rudimentary. I’m not afraid of the rudimentary; my life as inexpert painter thrills me as much as expertise ever did or will.

Writing and painting both are systematic investigations, using materials, supports, conventions, desires, and laws. Any action, in painting or writing, produces new exigencies, new emergencies. Dealing with those crises is enormously pleasurable; bumping into the conventions, encountering the supports, stretching or being stretched by the materials–these experiences are cozy because the writer or painter is not alone. The governing possibilities (encoded in line, color, support, image, space, texture; or in word, image, story, syntax, antecedent, genre, allusion) create hugs and rubbings and closures and gaps. I could be more explicit.

LT: Some of the work titles have references to dolmens, which, from what I know, are some sort of ancient tomb-like structures. Can you explain or shed more light on this reference? Also in some works like Dolmens in Gauzy Text Storm, there is actual text underneath paint. What text is this? Does the legibility of this text matter?

WK: Dunno how I stumbled on “dolmen.” I visited Stonehenge for the first time, last summer. Maybe that’s how. When I moved away from figurative painting, and started to be more abstract, I noticed that I was drawn to making compositions that included a central Being, like an obelisk, a lump, an animal, a statue, a totem, a featureless person, a rock or mountain…. I liked the stupidity and lumpiness of these figures, their non-personality, their resemblance to mineral or animal. Dolmen sounded like doll men. Fake little “men” without gender or job or speech. More girlboy than man or doll. These lumpy creatures grounded the painting’s abstraction; they were my little hero/ines. Maybe they were replacements for dead figures. Maybe the dolmen was a funerary monument. Or maybe the dolmen was just a stand-in for existence: existence’s body-double. Not unlike Harpo Marx. Mostly I like a painting to have a character in it, even if the character isn’t human. Sometimes the dolmen are plural: a tea-party, a summit conference, a family reunion. My “speedy fruit” paintings are dolmen-esque; but the speedy fruit, arrested in a landscape, still seem involved in an errand. They’re headed elsewhere. The dolmen aren’t going anywhere.

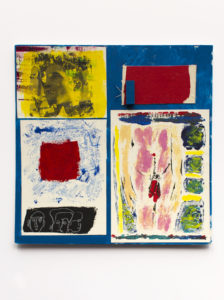

LT: Do you have a relationship to sculpture? I’m thinking especially about the works in the show that are paintings with sculptural references, or blue “masks”: Garden Rooms on Cardboard and Blue Pedagogy on Cardboard.

I wish I had more of a relation to sculpture. I’m trying! When I started stretching my own canvases, I developed a friendship with canvas-texture, and an understanding that the bumps in a canvas were my friends and allies. Working with those bumps – even when I’m painting on a wood panel or on paper, and need to create the bumps through surreptitious means – is a new vocation, a new support-group. The bumps are a step toward sculpture. I also like to paint on found supports –cardboard, Styrofoam, wood. Cardboard, especially. I found the cardboard strips (for Garden Rooms, Blue Pedagogy, and The Knob) in the garbage. The sidewalk was where I found the wood for Self-Portrait on Found Wood with Hole. I like collaging canvas scraps onto canvas. These techniques aren’t innovations, obviously –they’re rather tame, as experiments go. I’m just beginning to discover sculptural possibilities, which will, for me, probably remain in the realm of the micro: bump, groove, string. Minor excrescences, rising up from the surface. I do a lot of monoprinting in the studio–not with a press, just with my hands or a brayer. The experience of monoprinting is sculptural, because the printing agent has a physical solidity and trashy dispensability that frees me from taking too seriously the “result.” Oh, I’m back to rubbing again! Frottage. Is frottage sculptural?

LT: Your paintings and drawings play with both abstraction and figuration. Do you consider your works to have specific narratives?

Much of my work has been with male nudes. That’s a narrative. The guy taking off his clothes. The guy remaining unclothed. Drawing the guy. The guy ending up unrecognizable in his portrait. The guy in the photograph–if I’m using a photograph instead of a live model—is far away but graphically verifiable and easy to appropriate. The guy’s body is abstract because (Andy Warhol told me so) sex is abstract, and landscapes are nudes. A nude figurative painting contains these nervous plot-quandaries: is that guy me? is that guy a whole, or is that guy a set of parts? does the painting create a permanent bond between me and the guy?

Most of the work in this show is semi-abstract. The abstract work contains elements of nude figuration, but removed from the context of bodies. And my abstract work isn’t guy-oriented. It contains traces of guy but also of girl (woman) and girlguy or the places where gender isn’t organized and classifiable, or where genders overlap. Maybe that’s where my abstract paintings are happiest, in a world that’s concretely multi-gendered or fluidly gendered or mix-gendered: or where gender (and its narratives) is giddily multiple, and not as some abstract utopia, but as a tactile and imaginative experience that arises from specific encounters with line, color, composition, texture, and with various abuttings and simultaneities–as when, for example, three holes are friendly with a line that encloses or ropes them in but also emerges from them and finally is not distinguishable from them–or when, for example, a cabal of squares dotted with circles know their outlines but also ignore their outlines, which become the origin of new clouds containing Vs and chromosomal clusters.

LT: Ok, this last question is a little silly, but I remember reading “The Queen’s Throat” in grad school at Art Center and I have to say that it really compelled me to find my opera singer. Yours is obviously Anna Moffo (or Callas) and I spend a long time listening to so many different singers to find the one that worked best for me. I think its Mirella Freni. I went back to try and find any instances of you writing about her, but maybe you weren’t into her so much? Without being too presumptuous or weird, is there an equivalent artist or painter that’s like Anna Moffo to you?

WK: Thank you for mentioning Anna Moffo and Mirella Freni! Thank you for acknowledging their lustres. I heard Freni sing (live!) in Fedora at the Met: sumptuous sound. In 1996. It seems quite recent. Twenty years ago, Freni, in person.

Anna Moffo’s sound, in her brilliant prime, combined accuracy of pitch, fleetness of execution, ease of affect, and warmth of tone. The warm tone was the best part: molten and soulful and shockingly beautiful, like the earth inventing a new orange, or as if the rose or the poppy or the crocus had never been invented, and the universe was waiting for Anna Moffo to set these blooms in motion. The warm tone I’d compare to Joan Mitchell’s colors–her big paintings, like Minnesota, containing color so beautiful you want to give up on every other pleasure. The ease of affect–saying I’m right here, without complication–I’d compare to Robert Rauschenberg: he seemed to put out his goods with a gratified and generous abundance, not too much policing at the threshold. Fleetness of execution: Paul Klee. Lines and micro-instances of movement and murmur that are impossibly exact, quick, irreproducible. A skittering that’s never messy. A skittering that thanks you for observing it. Accuracy of pitch: B. Wurtz. The flotsam is placed where some divinity at the beginning of plastic’s Eden demanded that the flotsam be placed. Everything looks accidental and ordinary, but the perfection of its placement, and the humility of its manufacture (unaltered, unblessed), creates a new church of rescue, where objects never loved can find, in sight’s afterlife (which is right here, right now), a blessed containment.

Forrest Bess, Alice Neel, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Amy Sillman, Matt Connors, Glenn Ligon: artists whose work I’m always thinking about. Kandinsky, too. I could mention three hundred more. Gego. Maria Lassnig. Maureen Gallace. Marsden Hartley. Bill Traylor. Patricia Treib. Cy Twombly. Paul Mpagi Sepuya. Carolee Schneemann. Jean Dubuffet. Marco Breuer. Manuel Álvarez Bravo. Leeza Meksin. James Siena. Nell Blaine. Dieter Roth. Beauford Delaney. Adolph Gottlieb. Thank you to every artist who is making something right now. Thank you to every artist who is looking at something you just finished making and is enjoying the sensation.

- Select ReviewsPast Press

– -

Wayne Koestenbaum opening reception

March 19, 2016